我知道《紐約時報》早前已刊登了邵家臻的obituary , 但我總覺得那篇文章不夠 「到肉」,所以我這幾天自行寫了一篇我覺得更能反映邵的版本。它也適合對香港近年發生的事有好奇心的西方人看,如果大家生活中認識這樣的人,可以轉發。

“I’m 44. I should still have half a lifetime ahead of me, if you don’t mind my being too optimistic,” social worker and university lecturer Shiu Ka-Chun joked at the beginning of his speech on political activism at a Tedx event in 2014, the year of Occupy Central, a civil disobedience movement staged to pressure Beijing to live up to its promise of granting Hong Kong free elections.

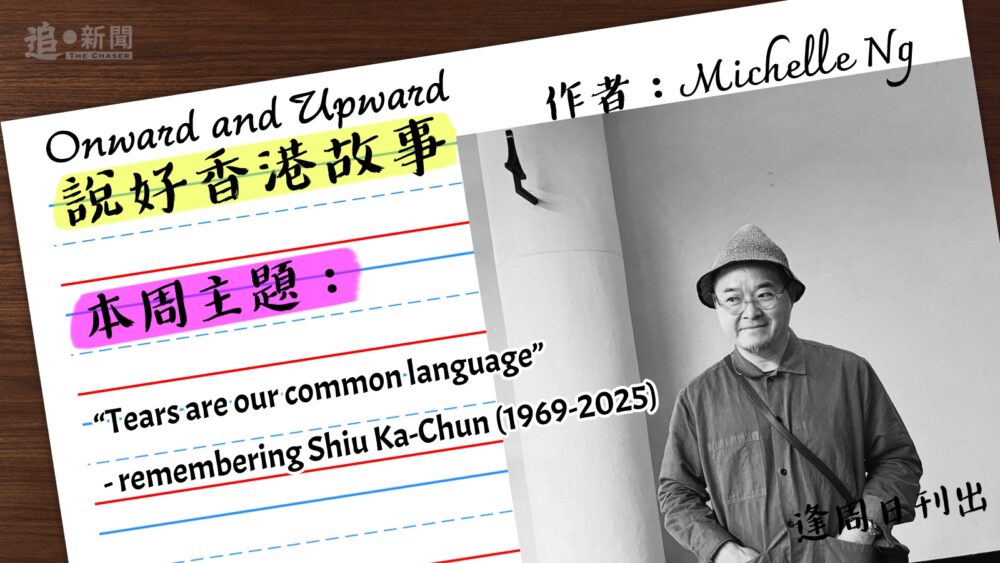

At the time, there was no way Shiu – a Christian who took on “Bottle” as his English name, a nod to his yearning to be God’s vessel – could have known he only had a decade left to live (he would die of stomach cancer on 10 Jan 2025). Still, he conducted himself as if he had known his remaining days on earth were limited, so wholly did he throw him into the battle to save Hong Kong from the grip of the Chinese Communist Party.

Two years after his speech, he put himself forward as a legislature candidate and won. In the spring of 2019, he was convicted of causing public nuisance for his role in Occupy Central. The eight-month sentence that was slapped on him turned out to strike at the most fortuitous moment. Inside the prison, Shiu got a taste of the deplorable living conditions designed to crush inmates into submission (for example, since ventilation was virtually non-existent, “the mere act of sitting was enough to make one feel like a bun in a steamer”). Outside the prison, in response to the Hong Kong government’s plan to enact a law that would extradite suspects to China, the people of Hong Kong staged a seemingly unending series of street protests that summer, the largest one involving two million in a city of seven. By the time Shiu was released, the government had begun arresting protestors (their numbers would eventually swell to over 10,000), and Shiu’s next role seemed cut out for him. Now stripped of his seat in the legislature – in the coming year he would lose his job at the university as well – he repurposed himself and set up Wall-fare, a prison advocacy group. Whether it was buying up packets of M&M’s chocolate that met the prison authority’s strict requirement, or delivering letters of support written by the public to detained protestors, no task was too small for Shiu, if it meant those locked up could be persuaded that they had not been forgotten. Before long, Wall-fare drew the ire of the Hong Kong government. Shiu was forced to shut it down nine months later. He sought comfort in studying theology. Asked by a reporter whether he was worried that from now on, prisoners would no longer have access to adequate aid, Shiu broke down, clasped his hands in front his face, and stammered “tears are our common language.”

The real wonder about Shiu is not that he managed to do so much in so little time, but that there was nothing in his upbringing to indicate he would one day have the guts to take on the world’s most powerful dictatorship. As a kid from a humble family, he was so lacking in assertiveness that while travelling on a bus, he had trouble pressing the “stop” button (“I didn’t think I was worthwhile for the bus to stop for”), yet as a fledgling political activist, he took the lead in raising his arms to dare the police to handcuff him. As an adolescent, his desire to join the police cadet program was never fulfilled because he was too chicken to walk into a police station and ask for an application form, yet during his spell in prison, he was so ready to object the many unreasonable rules that regimented every aspect of prison life that he filed a formal complaint 16 times, leading the guards to remark in jest “you’ve exhausted our entire supply of forms (complains are usually few and far between because inmates fear – rightly – that guards will make them pay in the future).

Shiu did give clues in his Tedx speech on how he was able to accomplish his 180-degree turn on the courage front. He was driven by the imperative of “forging ahead despite feeling fear acutely,” by his revulsion of those who, after allowing themselves to be ruled by fear, are reduced to “turning a blind eye to injustices that happen outside their self interests,” and by the weird sensation of “feeling most alive when one is fighting.” Most of all, he was driven by his conviction that no matter how many times his efforts failed, what he did still mattered – “there is no instant outcome, but there will be a distant impact”(無效果,有後果)was one of his mantras.

On 11 Oct 2024, Shiu noted briefly on his social media that he wasn’t feeling himself. Three weeks later, he gave a fuller account on what had transpired. Stomach had been acting up. GP said it was gastric acid. After a few days of violent vomiting, consulted a specialist. Was told it was stomach flu. Even more violent vomiting followed. Went to ER. Received stomach cancer diagnoses and got operated upon immediately.

On 9 November, Shiu updated his Facebook cover photo. It now featured a medium shot of a nondescript highrise at nighttime; beside the only lighted window was a speech balloon with only “me” in it. In the days and weeks that followed, he complained about the noise in the communal hospital ward he was in; he couldn’t sleep through the night. His operation – the removal of half his stomach and some neighbouring lymph nodes – was meant to pave the way to recovery, but it ended up depriving him of his bodily functions in quick succession. By December he had to be tube-fed. By early January he lost his ability to speak. Four days before his death, he had his last communion. Since eating and drinking was out of the question, his wife placed the cup and wafer next to his lips, as a way to allow him to partake of Christ’s body symbolically.

After Shiu’s passing, his theology professor Fuk Tsang Ying recalled having once brought him to a cemetery in Hong Kong where foreign missionaries are buried.There, Ying singled out the graves of Fritz Schlatter and Eric A. Wood, two European missionaries who either died of infectious disease on the passage to Hong Kong or passed shortly after arriving on its shores. Surely, Ying mused, in their last moments, they must have asked God “Why?” Perhaps Shiu, in his agony and endless sleepless nights, brooded on the same question.

I never met Shiu in person. If I had done so and had a friendship had been struck, I would have pointed out to him that my ear for the English language was certainly superior to his, and that “Bottle” wasn’t exactly an apt English name for him – the word carries the connotation of retreat and withdrawal, the exact opposite of what Shiu had been doing with his life. Now that he is no longer with us, nitpicking the usage of “Bottle” is not only meaningless but distracting. For Shiu has been a bottle of after all – that flask of expensive perfume Mary broke and poured over Jesus’ feet, only that from Shiu’s point of view, we and Hong Kong were the stand-in for Jesus, and so in pouring himself on us he was actually pouring himself on Him. Yes, little of what he did had an instant outcome, but after his death, judging from the outpouring of grief from the Hong Kong diaspora – those who have fled Hong Kong in recent years in order to continue living freely – the reach of his impact is very distant indeed.

Michelle Ng

英國牛津大學畢業,前《蘋果日報》和《眾新聞》專欄作家,現在身在楓葉國,心繫中國大陸和香港。

聯絡方式: michelleng.coach@proton.me

個人網站: https://michellengwritings.com

🌟加入YouTube頻道會員支持《追新聞》運作🌟

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC5l18oylJ8o7ihugk4F-3nw/join

《追新聞》無金主,只有您!為訂戶提供驚喜優惠,好讓大家支持本平台,再撐埋黃店。香港訂戶可分享給英國親友使用。