英國倫敦T Cribb & Sons殯儀館於1881年創立,旗下「國家葬禮博物館」(National Funeral Museum)與《追新聞》聯乘,介紹英國傳統殯葬文化,首集介紹「維多利亞時尚喪服」。

倫敦國家葬禮博物館策展人Minette Butler在倫敦瑪麗王后大學(Queen Mary University of London)修畢文化遺產管理,她重現維多利亞時期的貴婦喪服時尚。

在英國維多利亞時期,死亡幾乎充斥着每日的生活,殯葬文化也乘時興起。人們開始穿着「黑色葬服」懷緬至親,18世紀初期,英國隨着工業革命加促貿易發展,令富裕的新社會階層湧現。他們既沒有傳統的世襲爵位包袱,也受到當時的貴族排擠。不過,這群富裕階層開始模仿貴族時尚,從而切合他們的身份和地位。他們會在送殯隊伍中穿着黑色長袍,模擬貴族的「紋章葬禮」(heraldic funerals)。

英國寡婦一般需要守喪兩年,有時穿上黑色長裙更達4年。維多利亞女皇於1861年失去至愛艾伯特親王時,直至她於1901年駕崩,也一直穿上黑色長裙。

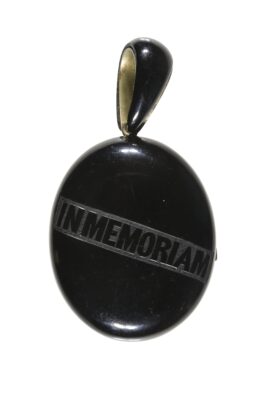

服喪期分為不各階段,至親遽逝時,親人穿着沉厚的暗黑色布料縫製的喪服,用「惠特比煤玉」(Whitby Jet)鑲造的珠寶。踏入「半喪期」,則可改穿用絲綢或蕾絲縫製的黑色喪服。在最後服喪階段,女士們可以選擇穿戴不同珠寶,用灰色或紫色布料製作的喪服。

喪服裁縫也鼓吹「迷信」,跟客人說保留或重穿喪服會帶來不幸,以確保穩定的客源。至於,喪服時尚並不限於權貴一族,英國基層也要為死亡作好準備,他們會定期課金給「殯葬會」(burial clubs),確保服喪期能夠有喪服穿上,也選擇到二手市場購買富人穿過的喪服,即使未能負擔全套喪服,也會花錢購買黑色臂帶或圍巾表達心意。始終,在舊時保守的社會,也要在乎別人的目光。

喪服時尚一直流行到20世紀,直至第一次世界大戰開始,超過88萬英軍魂斷沙場。在物資匱乏下,英國人不再奢求豪華的服喪禮儀。時至今日,出席喪禮者不會重返維多利亞時期般守喪數載,出席喪禮者雖然遵循傳統穿上黑色服以示尊重,但更多人生前要求親友在其葬禮上一反傳統舉行繽紛派對,以「慶祝短暫而熣燦的生命」。

倫敦國家葬禮博物館策展人

Minette Butler

(詳見【英文版】)

Dressed for Death: Mourning Fashion in Victorian Britain

In Victorian Britain, death was part of everyday life. Not only did people have shorter life spans due to disease and poor living conditions, but the country also took part in an elaborate culture of funerals and mourning. This included the custom of wearing “mourning clothes”, where people would spend months or even years of their lives dressed in special black garments to show their respect for lost family and friends.

※Elderly Woman in Mourning Clothes c1890 Wikimedia Commons ※英國婦人展現維多利亞時期的服喪時尚。 (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

European mourning clothes date back to Ancient Rome, where men would wear a dark wool Toga known as a “Toga Pulla” to show a family member had died. But in Britain, the custom of going into mourning’ developed from the fashions, etiquette and traditions of the social elite – particularly in the Royal courts.

In mediaeval times, the rich were entitled to special “Heraldic” funerals organised by a division of the Royal Household called the College of Arms. Reserved for people with “titles”, including royalty, knights and bishops, these funerals included a grand procession where mourners and attendants would wear long black robes. These contrasted with the brightly coloured banners carried ahead of the body, representing the deceased’s family Coats of Arms. If a person without titles was caught “copying” these types of funerals they could be heavily fined.

There were also special “sumptuary” laws that restricted what types of clothes people could wear depending on their social status. The custom of wearing dark clothing to acknowledge death and grief was reserved for royalty and the upper classes – only the highest ranks were allowed to wear black or purple (though lower classes were allowed to wear more affordable colours like brown, grey or white to funerals). The styles of these mourning clothes, such as the length of the cloaks and their hoods, also depended on your rank. Again, if you were caught wearing mourning clothes reserved for those above your station you could be heavily fined.

However, by the early 1700s these traditions began to change. New social classes gained wealth and status from growing trade and commerce and, without traditional titles and inherited rank, they were not welcome in aristocratic circles. However, they decided to copy the nobility’s popular fashions and etiquettes to assert their new rank and prosperity. Though initially held back by the “sumptuary laws”, these restrictions were gradually abolished as the new classes gained importance in high society and government.

※Heraldic Funeral with Black Mourning Robes c. 1603 Funeral of Queen Elizabeth I ※伊利莎白女皇於1603年國葬規模。(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

Not only did this include wearing long black robes in funeral processions, designed to imitate elite “heraldic” funerals, but also the custom of “going into mourning”, where the Royal Court would wear black to acknowledge the death of a family member or other European royalty. Often lasting for several weeks, months or even years, it followed a strict set of rules on what people could and could not wear – restricting courtiers to only wearing black dresses, coats and accessories in palaces and other royal spaces.

As class restrictions relaxed, this etiquette was copied into public magazines like household guides and ladies papers, and the new classes eagerly adapted the customs into their own lives and deaths.

These guides offered clothing advice for every kind of loss – from close family members like parents and children or husbands and wives, all the way to distant cousins and family friends.The closer you were to the deceased meant the longer you mourned. For example, the deaths of distant relatives only required four to six weeks in black, whereas closer relations like the loss of a mother or father were observed for up to a year. The longest period was for widows, who were expected to wear black for at least two years and could carry on mourning for up to four. After she lost her husband in 1861, Queen Victoria would wear mourning clothes until her death in 1901.

※Queen Victoria Mourning Gown post 1861 Wikimedia Commons Public Domain ※ 維多利亞女皇直至駕崩仍穿上喪服。(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏)

Mourning was also split up into “stages” that changed what you wore as time passed. This started with “First” or “Deepest” mourning, which began as soon as a person had died. Here, you could only wear dull black fabric – usually a heavy, crimped material called “crape” – with no shiny materials or colours. If you wore jewellery, it had to be special “mourning” jewellery that was usually made from Whitby Jet, which was a kind of black fossilised wood mined from the Yorkshire coast that was carved into beads, brooches and other accessories.

※Jet Locket Pendant National Funeral Museum Collection reads IN MEMORIAM ※ 服喪吊墜用黑色「惠特比煤玉」為潮流之選。(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

After a period of time you would move on to “Second” or “Half Mourning”, where you could wear more elaborate black fabrics like silk or lace. After this period was over you would go into the last stage – “Third” or “Ordinary” Mourning, where you could wear different jewellery, fancier fabrics and even certain colours like grey or purple.

Exact advice differed depending on which magazines or books you read, and these stages and time periods depended on your relationship with the deceased. For example, widows were expected to wear “deepest” mourning for at least one year, while others may have gone straight into “Half” or “Ordinary” mourning if they were not closely related to the deceased, such as a distant aunt or uncle.

This etiquette mainly applied to women. In Victorian times, most men already favoured black or dark coloured coats and would simply change to black gloves, hat bands and buttons when someone died. Meanwhile, Victorian ladies loved wearing bright colours and elaborate patterns, so changing to wearing only dull black was a visible and drastic shift. Mourning periods were also longer for women than men. While Widows would be dressed in black for at least two years, men who lost their wives would only wear mourning for one year.

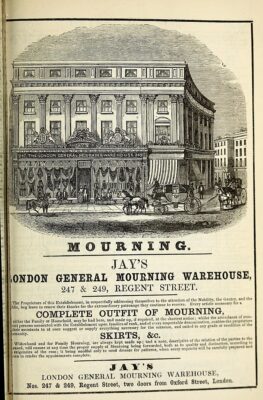

But all of this etiquette did not stop people from following fashion. Many women would have their dressmakers tailor their mourning clothes according to the latest styles and silhouettes. By the 1840s, special department stores known as “Mourning Warehouses” opened up in cities like London, designed just to sell mourning clothes. With enormous catalogues that provided advice on proper etiquette for every kind of loss, these shops kept up to date with fashions from Paris and Milan by advertising clothing that was flattering and in vogue with the newest trends. “Second” and “Ordinary” mourning clothes could be just as elaborate as normal fashion – decorating dresses with intricate designs using feathers, beads, ribbons and lace.

※ Jays Mourning Warehouse London Advert c 1860 Wikimedia Commons ※ 倫敦Jays於1860年宣傳殯儀用品生意廣告。(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏)

Mourning could be expensive. Not only were you expected to set aside your normal clothes to buy a whole new wardrobe, but these new garments were very rarely reused once the period was over, especially amongst the fashionable middle classes. By the time a family experienced another loss, trends had moved on and the style had become out of date. Most would not want to be seen wearing ‘old’ fashion, even if it was meant to show respect for the dead.

Mourning Warehouses would even encourage the superstition that it was bad luck to keep old and used mourning clothes. This ensured that you would need to come back again and buy new black dresses and coats the next time someone died. That way the shop would get a steady supply of “repeat” customers.

Despite the expense, mourning fashions were not just for the rich and elite. Even the poorest in British society would set money aside for their deaths, making regular payments into “burial clubs” that would fund their funerals. This included providing money for mourning clothes. There was a second hand market where you could buy wealthier people’s used garments, but even if you could not afford a full outfit, people would spend what little they had on black armbands or scarves to show that they were in mourning.

As well as wanting to show their grief and respect for their lost loved ones, there was a lot of social pressure on poorer people to seem ‘respectable’. Many people feared judgement for not “caring” enough about their dead if they did not observe the mourning period. Keeping up with this complex etiquette was an important way to show you were “decent” and had “done right” by your family – even if it could make you bankrupt.

Mourning fashions would last until the early 20th century, but they would go into decline at the start of the First World War. With over 880,000 British forces dying between 1914-1918, it was seen as wasteful and indulgent to spend valuable resources on special mourning clothes and draw attention to your own loss in the face of such widespread death.

Although the custom of wearing black to funerals largely continues in the UK to this day, most people are not expected to “go into mourning” like they were in Victorian times. In fact, many have begun to request people wear bright colours to their family’s funerals instead – rejecting the traditional atmosphere of solemn grief in favour of a brighter and simpler “celebration of life”.

Minette Butler – Curator, National Funeral Museum

倫敦國家葬禮博物館(National Funeral Museum)

Twitter: @nfmtcribb

Instagram: @nationalfuneralmuseum

地址:T Cribb & Sons, Victoria House, Beckton, E6 5PA

開放時間:周一至五,上午9時至下午5時

歡迎團體或個人預約,館方安排免費導賞服務,請電郵至nfm@tcribb.co.uk