英國倫敦T Cribb & Sons殯儀館於1881年創立,旗下「國家葬禮博物館」(National Funeral Museum)與《追新聞》聯乘,介紹英國傳統殯葬文化。

英國維多利亞時代,葬禮講究排場,一場豪華又隆重的儀式少不了馬車、豪華棺木,以及天鵝絨棺罩。送殯過程一般由禮儀師帶領,家屬步行或坐在馬車內尾隨,途人看到送殯行列經過時,都會停下腳步行鞠躬禮。倫敦國家殯儀博物館(National Funeral Museum)收藏維多利亞時期的一對權杖,也顯得彌足珍貴。

葬禮權杖約30寸長,在金屬上雕刻和裝飾,一般由禮儀師手執權杖護送靈柩到教堂。在英國,扶靈隊伍送殯儀式可追溯至中世紀,由皇家紋章院(Royal College of Arms)負責國葬安排,英格蘭、威爾斯、北愛爾蘭,以至大部份英聯邦國家,都設有嘉德首度紋章官,主要是為英國君主在禮儀方面的主要顧問,當中包括每年國會開幕大典,以至今年5月英皇查理斯三世加冕禮,都看到紋章官的身影。

不過,皇家紋章局只為社會上流階層服務,除了皇室成員外,也會為騎士、伯爵,以至教皇籌備儀式。「紋章葬禮」由逝者的家中出發緩緩走到教堂,由家族繼承人或摯親帶領行列,徽章代表逝者家族的標記,也是一種「成就」。今時今日的教堂,頭盔會懸掛在逝者埋葬的教堂地窖的墳墓下,用以紀念其一生的成就。

傳令官(Gentleman Ushers)作為僕人的最高級別官員,通常穿上全黑色,手持「白杖」,而嘉德勳章成員作為英國榮譽最高級別的騎士勳章,在送葬儀式上也遵從傳統行規,權杖與維多利亞時期的權杖設計也十分接近。

由於英國很多人有錢人沒有家族世襲勳銜,但也想擁有「紋章葬禮」,17世紀前,法律明文禁止任何人盜用紋章學院的規格和儀式,否則將施以重刑。後來,紋章院失去權力追查模仿者,畫家、木匠和傢具工匠紛紛製作棺木,提供「紋章葬禮」的二創裝飾。禮儀師開始為客人提供更多配件,包括馬車、絲絨蓋棺等,令送殯儀式媲美「紋章葬禮」般華麗隆重,雖然沒有「紋章院」加持,但也令到葬禮更為莊嚴和具儀式感。

權杖重量既沉重,也具一定威懾的武器,「紋章葬禮」的權杖也擔以重任,保護着遺體由送殯過程、入土為安的全部過程,在大型的紋章葬禮儀式中,歷史學者認為權杖有助消減人們對死亡的恐懼。

在維多利亞時期,專業盜墓者趁深宵時分潛入教堂墓園,掘起新墳偷屍送到大學或醫學院,為醫生和醫科生提供遺體學習解剖並研究人體結構。由於解剖人體與基督宗教信仰存在矛盾,基督徒相信死後需要肉身才能復活,過去偷屍解剖人體的懲罰與謀殺無異。摯親為杜絕盜墓者,除了聘請守墓人全天候保護墳墓外,有家屬租用稱為「死亡保險箱」(Mort Safes)的大型鐵籠罩着墳墓,確保屍體徹底腐化歸於塵土。

葬禮權杖用途,明顯是用來震懾,以阻嚇試圖劫屍賊襲擊送殯隊伍前往墓園,因為屍體愈「新鮮」叫價愈高,所以家屬擔心途中遇到劫屍賊。 與很多殯葬傳統一樣,權杖開始在20世紀初期不再流行。今時今日,很多送葬配備已不合時宜,縱然殯儀公司仍然提供這些配件,但送葬者也不知道紋章的復雜歷史和繁文縟節,仍然保留下來只不過令到葬禮更具儀式感和瀰漫着奢華的氛圍。

倫敦國家葬禮博物館策展人

Minette Butler

(詳見【英文版】)

Funeral Truncheons and the Art of Undertaking

In Victorian Britain, funeral furnishing was a serious and elaborate business. The most expensive ceremonies included beautiful horse drawn hearses with richly decorated coffins and velvet palls. These processions were escorted by a solemn undertaker through the quiet streets with great respect. The deceased’s family would follow behind either on foot or in special horse drawn mourning carriages. When you saw one of these grand parades pass by, you were expected to stop and bow your head.

- 送葬權杖 Funeral Wand (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

- 送葬權杖 Funeral Wand (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

At the National Funeral Museum we have another essential accessory seen at many upper-class Victorian funerals. This is a pair of batons or “funeral truncheons”. Measuring about 30 inches long, they were carefully carved and ornately decorated with metal fixings. They were carried one each by the undertaker’s attendants who would walk either side of the body as it moved towards the church. Often accompanied by other attendants carrying “funeral wands”, a similar pair of simpler black canes, these were an expected and imposing part of any respectable funeral well into the early 20th century.

啞巴帶領送殯隊伍。Funeral Mutes leading a procession c. 1733 (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

In the UK, carrying staffs in a funeral procession dates back at least as far as mediaeval times – specifically, in the traditions of funerals arranged by the “Royal College of Arms”. This is a division of the Royal Household that still exists today, acting as the “heraldic authority” for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and much of the Commonwealth. They mostly oversee the recording and granting of new coats of arms as well as taking part in ceremonies like the Annual State Opening of Parliament. You may have seen the Heralds last month taking part in the Coronation of King Charles III.

But the College of Arms also used to oversee the funeral arrangements of society’s most elite. Known as “Heraldic” funerals, these services were expensive and reserved just for people with family titles and coats of arms. This not only included the royal family, but also other elites like knights, counts and bishops.

T Cribb & Sons 殯儀師手持權杖帶領送葬隊伍。

T Cribb & Sons Procession carrying Funeral Truncheons c. 1900 (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

These funerals were colourful pageants of pomp and ceremony. Attended in person by the heralds, the funeral centred around an elaborate procession from the deceased person’s house to their local church for the burial service. All ranks were invited to take part, with the poorest leading the parade and the deceased’s family followed behind the body, led by their heir or closest relative as “Chief Mourner”.

Just ahead of the body, the heralds would carry representations of the deceased’s Coat of Arms. Known as “achievements”, these included painted banners and flags as well as specially made armour used just at the funeral. Achievements like funeral helmets can still be found in churches to this day. These were hung near where the person was buried under the church floor to act as a kind of memorial.

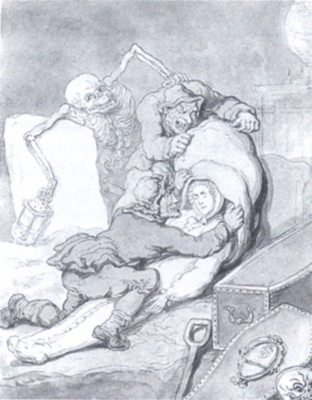

18世紀人們相信靈魂復活。

resurrection men c 18th century Wikimedia Commons(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

But more than achievements, the heralds themselves lent prestige and authority to the funeral service, dressed in long black robes with bright and richly decorated tabards coloured red, blue and gold. But they weren’t the only attendants in the procession. The heralds were accompanied by Gentleman Ushers who were the most senior rank of servant found in both royal and noble households that served the deceased during their life. Also dressed in black, they stood out by carrying special “white rods” or staves which represented their senior rank in the deceased’s service.

Furthermore, members of the historic “Order of the Garter” known as the “Knights Companions At Arms”, the most senior order of knighthood in the United Kingdom, would walk in certain funeral processions carrying traditional batons – heavier than staves and usually more decorated. These rods and batons are very similar to the Victorian wands and truncheons.

Accessories like achievements and rods, as well as the presence of the heralds and their traditions of state and power, were solemn and impressive. This meant many people without family titles wanted to have their own “heraldic” funerals. However, before the 17th century there were laws that meant anybody caught copying the style and furnishing used by the College of Arms could be heavily prosecuted. They also monitored lower titles in case they held funerals ‘above their station’, such as having too many achievements for their rank or the wrong coats of arms. These traditions were controlled to maintain the rigid class structure that kept mediaeval and early modern society in check.

保險箱保護遺體

Mortsafe – placed over a fresh grave to protect the corpse from body snatchers Wikimedia Commons(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

But soon the College of Arms lost the authority to chase after these imitators. Gaining a reputation for overcharging noble families, they had to compete with a new, growing trade known as “Undertaking”. These were sign painters, carpenters and furniture makers who offered to make coffins and provide the elaborate furnishings traditionally seen in heraldic funerals.

Initially they catered to the noble elites who wanted a better price, but soon they began appealing to the new and rising merchant classes. These families had no inherited titles and therefore would not be entitled to the Royal College of Arms’ services. However, Undertakers were more than willing to provide all the expected accessories for their new clients. This included horse drawn carriages to carry the body, a velvet pall to cover the coffin and attendants to escort the procession to the churchyard.

But undertakers also got creative. Though these families had no coats of arms to carry as achievements, they made new accessories that could lend an atmosphere of pomp and ceremony. The traditional funeral helmet became dyed black ostrich feather plumes which were worn by the horses or carried on top of the coffin or even on an attendant’s head. The heraldic castle guards who traditionally stood by the body became funeral “mutes”, which were professional mourners dressed in black that led the procession and guarded the deceased’s home in solemn silence, each carrying tall black staffs.

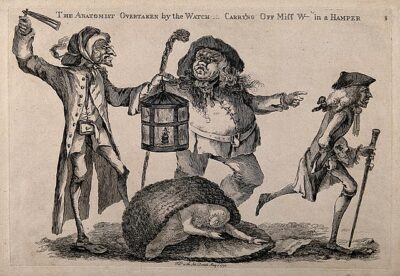

守墓人發現盜墓者將遺體藏身竹籃內

Nightwatchment discover body snatcher hiding a corpse in a basket c. 1773 Wikimedia Commons(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

So this practice of copying heraldic funerals is likely where our funeral truncheons came from. Undertakers armed their attendants with imitation wands and batons to copy the accessories carried by Knights Companions and Gentleman-Ushers. An imposing sight, the men walking either side of the coffin with these accessories lent an atmosphere of authority and ceremony to any funeral that could afford their services.

Truncheons are heavy and threatening weapons, and in heraldic funerals the similar batons ritually represented the defence of the dead person’s body. Though this was largely ceremonial in heraldic processions, some historians have suggested that the truncheons also repelled one of the greatest fears and taboos about death in the 19th century.

Perhaps the biggest anxiety held by the living once their loved ones were in their graves was the work of the “Resurrection Men”, also known as the “Body Snatchers”. These were professional gangs who stalked the churchyards at night, digging up fresh graves to take the newly buried bodies to local universities and medical schools. Here doctors and students would dissect these corpses to learn anatomy and research how the human body works.

Though a necessary part of medical science, dissection contradicted people’s deeply held religious and social beliefs about the human body – particularly the belief that the body was needed after death for christian resurrection. Dissection had also been used as a punishment for murder, which associated the process with reprimanding and deterring criminals. People would go to great lengths to keep body snatchers from their loved one’s graves. Many employed night watchmen to guard the body, while others rented large iron cages called “Mort Safes” to place over the grave until the corpse had decayed beyond use.

This fear and these measures have led to a popular belief that funeral truncheons were used as an extra deterrent to ward off anyone who tried to attack a funeral procession on the way to a gravesite. The ‘fresher’ the body meant the higher price it could fetch, so many feared that Body Snatchers would try and steal the corpse from the hearse before it was even put in the ground.

However, there is no evidence that truncheons were ever officially wielded as a weapon and they were generally used before and after the peak of the body snatching trade. In fact the truncheon’s origins, as well as the origins of many other great funeral traditions like mutes, palls and ostrich feathers, had faded out of popular memory by the end of the Victorian era. Many undertakers regularly furnished funerals with these accessories with no idea about their complex heraldic history – instead, they were used because they were expected and they encouraged an atmosphere of impressive ceremony and luxury.

Like many funeral traditions, truncheons and wands fell out of popular use by the early 20th century. Though many survive as curiosities in family funeral directors or museum collections, they disappeared from the streets in favour of simpler services with less elaborate accessories. Today they remain a relic of the fascinating and often unusual Victorian way of death.

Minette Butler – Curator, National Funeral Museum

倫敦國家葬禮博物館(National Funeral Museum)

Twitter: @nfmtcribb

Instagram: @nationalfuneralmuseum

地址:T Cribb & Sons, Victoria House, Beckton, E6 5PA

開放時間:周一至五,上午9時至下午5時

歡迎團體或個人預約,館方安排免費導賞服務,請電郵至nfm@tcribb.co.uk