英國倫敦T Cribb & Sons殯儀館於1881年創立,旗下「國家葬禮博物館」(National Funeral Museum)與《追新聞》聯乘,介紹英國傳統殯葬文化。

維多利亞時代的英國,提醒世人「死亡」近在咫尺。社會瀰漫着哀傷的氛圍,由度身訂造喪服的專門店,到黑羽毛和天鵝絨裝飾的殯儀馬車,另有悼念珠寶、無數的書籍、戲劇、版畫討論折哀方法等等。倫敦國家殯儀博物館(National Funeral Museum)收藏一系列古董鼻煙盒,由木製、黃銅,以致珍貴的象牙製作,當中最特別是微型棺材的造型,十分珍貴。

鼻煙盒用來存放煙草,由公元前100年至1年在中美洲種殖廣泛種植。約1528至1533年經西班牙探險家傳入西歐,煙草獨特的香味和尼古丁成份,令人一試上癮,並廣泛用於藥物用途。那時候,煙草只限於富人的奢侈消費品,但時遷世易,煙草價格下降令煙草普及化。

今時今日,煙草成為煙斗或香煙原材料,而吸煙方法層出不窮。有人將煙草索入鼻腔內,有人將少許的煙草粉放在手背或特製的小匙,存放在設計華麗的鼻煙盒內。有錢人負擔得起用黃銅、白銀製作的小玩意,再鑲嵌搪瓷或寶石,窮人則使用木製或骨製的鼻煙盒。

鼻煙盒造型千奇古怪,有動物、貝殼或鞋為概念,另一款較受歡迎的是六面棺材造型。這個「小棺材」提醒「勿忘終有一死」(Memento Mori)。這些鼻煙盒通常會隨身攜帶,或放在枱頭,尤其在20世紀,棺材鼻煙盒在水手、士兵,以及戰犯之間十分流行。

倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏棺材造型的鼻煙盒,則追溯至第一次世界大戰。這個設計獨特的鼻煙盒用子彈殼製成,蓋子用軍服鈕扣,是英法大戰士兵製作「戰壕藝術」的紀念品。許多棺材造型的鼻煙盒為紀念陣亡的士兵製作,在戰場壯烈犧牲或船隻覆傾溺斃,鼻煙盒成為他們唯一擁有的「棺材」。

骷髏主題設計仍然仍為墓碑或印刷品的最重要主題。小小的鼻煙盒,成為最後埋葬的歸宿。 最初的棺材只是一個長方型盒,16世紀,英國棺木工匠打造六邊形。不少人選擇用兩個棺木,第一個棺木用榆木或松木這類輕身木材製造。出殯前,家人將遺體淨身後放入這個輕身棺材內,外層的棺木才是精心打造,用堅硬的橡木製作。

鼻煙盒的設計和裝飾都依據當時的流行時尚,少數髹上黑色並配以絲絨。不少鼻煙盒還有一個小名牌,以盾型或稱「棺材傢具」,刻上逝者的名字、年齡、死忌,讓親人能夠為摯愛紀念。「棺材傢具」包括金屬手柄,用來帶起棺木,以花卉圖案或紀念碑點綴棺蓋,鼻煙盒放在馬車後座上也不會感到格格不入。

很多人講究設計有趣,大多帶有滑動蓋和隱藏的隔間,設計成小拼圖盒供主人把玩,還刻上幽默雋語,例如抽出時露出火柴雕刻的骷髏,以及內藏煙草小遊戲。今時今日,英國古董店有琳琅滿目、不同造型的鼻煙盒,大家不妨一探當中的歷史小故事。

倫敦國家葬禮博物館策展人

Minette Butler

(詳見【英文版】)

Coffin Snuff Boxes: A Victorian Novelty

In Victorian Britain, reminders of death were everywhere – from enormous warehouses designed to sell special mourning clothes to elaborate horse-drawn funerals decked in black feathers and velvets. There was special mourning jewellery to wear and hundreds of books, plays and prints that discussed ways to cope with grief and loss.

「塵歸塵、土歸土」鼻煙盒。

Ashes to Ashes Dust to Dust Snuff Box

(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

However, the realities of life and death manifested in other, stranger ways. Here at the National Funeral Museum, we have a collection of antique snuff boxes. Coming in all styles and sizes and made of everything from wood to brass to ivory, all of them are shaped like miniature coffins.

Snuff is made of ground tobacco leaves. The plant had been used in Central America since the first century BCE, but it was imported to Western Europe by the Spanish in around 1528-1533. It became popular for its scent and addictive nicotine content, as well as being used for medicine. It was originally a luxury good reserved only for the wealthy, but as time went on the product became cheaper and more accessible across the social classes.

Though today tobacco is usually smoked in pipes or cigarettes, another one of the most popular ways to consume it was through the nose. Small pinches of the powdered leaves were sniffed on the back of the hand or even using special small spoons. The powder itself was stored in special boxes. More than practical containers, many were designed to be ornate and decorative. The rich could afford beautiful pieces made of brass and silver with intricate details like engraving, enamel or precious stones, but even poorer people would make their own novelty boxes from wood and bone.

Yet amongst the countless examples of painted lids and unusual shapes, like animals, sea-shells and shoes, one of the most popular snuff box designs was the traditional, six-sided coffin.

This may come across as morbid or grim, but these boxes were part of a longer attitude towards death in the UK. These little coffins were a kind of “Memento Mori”, which translates from Latin to mean “Remember Death” or “Remember You Must Die”. In Medieval England, people would often wear jewellery or display paintings and sculptures that depicted symbols of time, death and decay. This could include hourglasses, skulls and even human corpses.

These represented the inevitability of death as well as the Christian belief that life on earth is temporary and inconsequential compared to the afterlife.

While Memento Mori art had faded away by the Victorian era in favour of more sentimental mourning fashions, which focused on grief and affection rather than grim macabre, the motif did not disappear. Skull motifs could still be found on gravestones and in prints and papers, and meanwhile these strange little snuff boxes, shaped like the last containers for the dead, were carried in pockets and kept on table tops.

Coffin snuff boxes were most popular with soldiers, sailors and prisoners of war, even into the 20th century. One of the more curious examples from the museum’s collection dates back to the First World War. Made from a bullet casing with a uniform button on the lid, it was an example of “Trench Art” made by soldiers fighting in France and Belgium. Many people who found themselves in these conflicts may have found snuff boxes like these cathartic – an ironic way to express the danger they faced every day. Also, many coffin snuff boxes may

have been made in memory of fallen comrades. Lost on the field of battle or over the side of the ship, the snuffbox may have been the only “coffin” they would ever have.

The most interesting aspect of these snuff boxes is that, despite their often crude designs, many resemble real Victorian Coffins. In mediaeval times, being buried in a coffin was something only the rich elites could afford. Instead, most people were buried in fabric shrouds and carried from their homes to the church in a “Parish Coffin” – a container shared by the community to help transport the dead with dignity. Eventually coffins became more affordable and were built by local carpenters. Many of these carpenters would go on to specialise in furnishing funerals and became known as “Undertakers”.

Early coffins were simple rectangular boxes, but in the 16th century English coffin-makers began to favour the six-sided hexagon design to accommodate the shape of the upper body.

Most people were buried in two coffins. The first was plain and made of a lightweight wood like elm or pine. The body would be placed inside this first coffin after it had been washed and prepared to lay at home before the funeral. The second coffin was more elaborate.

Made of heavier wood like oak, the smaller coffin would be placed inside the larger coffin on the day of the funeral.

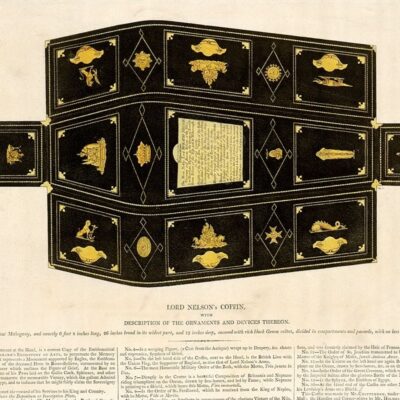

You can see some of the common designs and decorations for these coffins on these snuff boxes. A few are painted black to resemble velvet fabric, which was attached to the wooden coffin like covers for chairs and other furnishings. Many also include large studs or nails.

These were designed to attach the fabric but were also decorative and glinted in the candle light.

Many snuff boxes also include small name plates. Usually shaped like shields and known as “Coffin Furniture”, they were engraved with a person’s name, age and date of death. In an era when not everyone could afford their own memorial, this was often the only way a family could commemorate their loved one’s identity.

Other pieces of coffin furniture include metal handles, used to help carry the coffin, as well as decorative plates shaped like flowers or monuments to embellish the lid and sides. Many of our snuff boxes would not look out of place in an undertaker’s shop or on the back of a horse drawn hearse.

But more than being fascinating little models of real British coffins, these snuff boxes were not made to solemnly discuss death or preserve funerary art. In fact, many people bought, made and used them simply because they thought the boxes were funny. Most are built with sliding lids and hidden compartments, designed to act like little puzzle boxes for the owner to play with. Others even include humorous hidden details, like sliding drawers that reveal little corpses and skeletons carved out of lead or matchsticks. One coffin even has a name plate

裹屍布

Man wrapped in burial shroud Wikimedia Commons(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

reading “SNUFF IT” – a play on the box’s tobacco based contents and an old English euphemism for death (like “snuffing out” a candle).

These boxes were so popular that they even made an appearance in one the most famous British Victorian Novels. In Charles Dickens’ book ‘Oliver Twist’ the title character goes to work for the undertaker “Mr Sowerberry”, who offers a pinch of snuff from a box that looks like “an ingenious little model of a patent coffin”.

You can still find many examples of these snuff boxes scattered across antique shops in the UK to this day. Snuff is rarely used in the modern world, but these objects remain an odd and even fun curiosity. Their strange design and morbid content shows us how death permeated British culture even at the smallest levels. More than elaborate rituals and fashions that followed the deaths of family and friends, its symbols and tools could be found in ordinary people’s pockets – a witty and ironic token that sat in the background of everyday life.

- 棺木 Parish Coffin Wikimedia Commons(Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

- 鼻煙盒暗藏機關 Puzzle box snuffbox (Credit:National Funeral Museum Collection 倫敦國家葬禮博物館收藏 )

Minette Butler – Curator, National Funeral Museum

倫敦國家葬禮博物館(National Funeral Museum)

Twitter: @nfmtcribb

Instagram: @nationalfuneralmuseum

地址:T Cribb & Sons, Victoria House, Beckton, E6 5PA

開放時間:周一至五,上午9時至下午5時

歡迎團體或個人預約,館方安排免費導賞服務,請電郵至nfm@tcribb.co.uk